Global Goals, Local Change

A commitment to reach ambitious global health targets and a new community health system helped Ethiopia dramatically reduce childhood deaths.

I remember the disturbing images from Ethiopia of the 1980s when more than one million people died in a famine that swept through the Horn of Africa. It was a tragedy brought to the world's attention by the 1985 Live Aid concert and part of a long period of war, political unrest, and instability for Ethiopians. Their country ranked near the bottom on nearly every key health indicator, including child mortality.

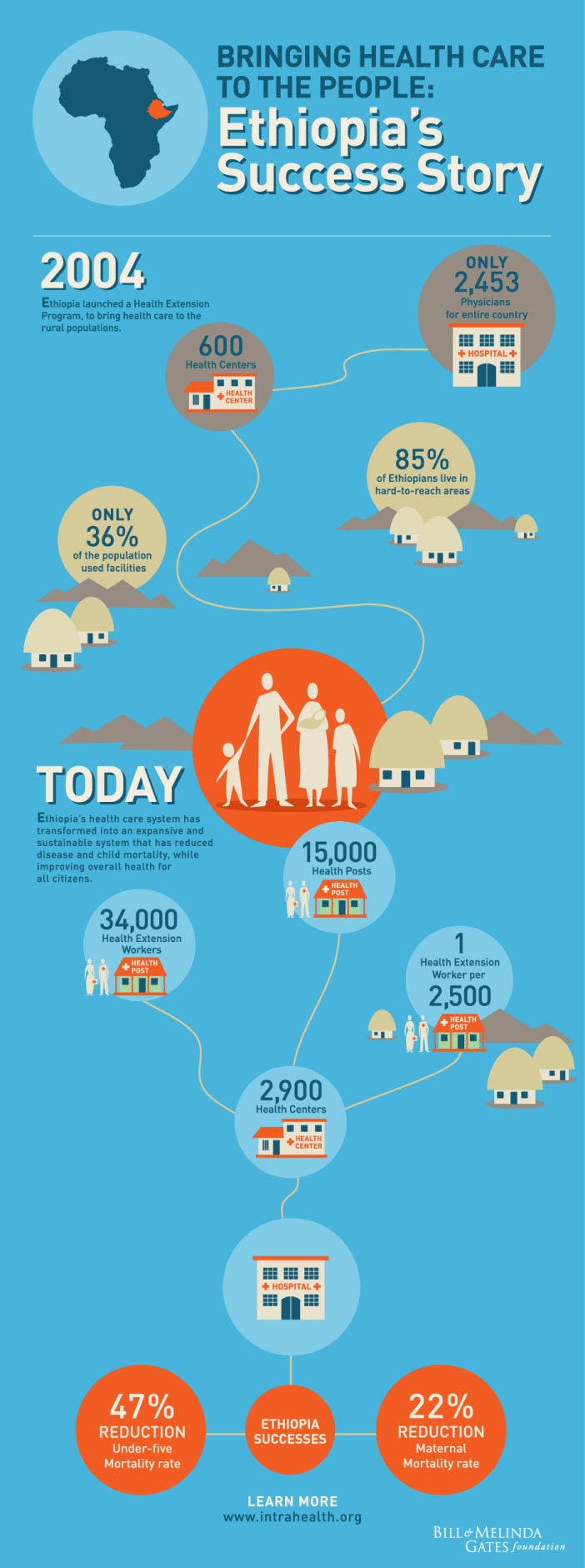

About a decade ago that picture started to change-thanks in large part to a government goal to bring primary health care to all Ethiopian citizens. When Ethiopia signed on to the MDGs in 2000, the country put hard numbers on its health ambitions. The concrete MDG goal of reducing child mortality by two-thirds created a clear target for success or failure. Ethiopia's commitment to the MDGs attracted unprecedented amounts of donor money to help improve its primary health care services.

Ethiopia found a successful model for achieving this goal in the Indian state of Kerala, which had lowered its child mortality rate and improved a host of other health indicators, in part through a vast network of community health care posts. This is one of the benefits of measurement-the ability it gives government leaders to make comparisons across countries, find who's doing well, and then learn from the best. With help from Kerala representatives, Ethiopia launched its own community health program in 2004.

Today, Ethiopia has more than 15,000 health posts delivering primary health care to the farthest reaches of this rural country of 85 million. They are staffed by 34,000 health workers, most of them young women from the communities they serve with one year of basic health training.

In 2009, Melinda traveled to Ethiopia and saw how these health reforms were transforming the country. Where health services were once nonexistent, rural areas had health clinics stocked with vaccines and medicine. Where once there was little local health expertise, Melinda learned how health workers delivered babies, administered vaccines, and supported family planning.

I got the chance to see that progress on my first trip to Ethiopia last March. Driving through the countryside, I felt the challenge Ethiopia faces in connecting its people to health care. Rural Ethiopia is composed of vast tracts of farm land-85 percent of the population survives on farm plots of less than two acres-connected by sometimes very rough roads. On the way to the Germana Gale Health Post, I saw piles of teff, a grain used to make Ethiopia's spongy flatbread, and I saw people walking everywhere. There were few other vehicles, even few bicycles.

The post, a faded-green cement building, was bigger than I thought it would be, and you could tell workers took great care of the place. Inside, two health workers showed me a well-stocked cabinet of the tools of their job, including folic acid, Vitamin A supplements, and malaria drugs.

The workers provide most services at the post, though they also visit the homes of pregnant women and sick people. They ensure that each home has access to a bed net to protect the family from malaria, a pit toilet, first aid training, and other basic health and safety practices. One health worker told me she had done 41 deliveries so far that year, most of which were performed at people's homes.

All these interventions are quite basic, yet they've dramatically improved the lives of people in this country. Childhood death has decreased. So has the number of women dying in childbirth. More women have access to contraceptives to plan if and when they want to have children. Melinda has been leading the foundation to strengthen our commitment to family planning (see her feature below).

Just consider the story of one young mother from Dalocha. Sebsebila Nassir was born in 1990 on the dirt floor of her family's hut. With little access to lifesaving vaccines or basic health care, about 20 percent of all children in Ethiopia at that time did not survive to their fifth birthdays. Two of Sebsebila's six siblings died as infants.

Ethiopia’s effort on health has lowered child mortality over 60 percent since 1990.

But a few years ago, when a health post opened its doors in Dalocha, life started to change. For the first time, she had access to contraceptives, so she could have children when she and her husband were ready. When the time came last year and Sebsebila became pregnant, she received regular check-ups from her health worker. The worker also encouraged her to have the baby at a local health center, instead of at home where she gave birth to her first child.

On November 28, the day Sebsebila went into labor, she traveled by donkey cart to the health center. There, a midwife was at her bedside during her seven-hour labor. Shortly after her daughter was born, the baby received vaccines against polio and tuberculosis. The health worker also handed Sebsebila an immunization card with a schedule for her daughter to receive vaccinations to protect her from diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, meningitis, pneumonia, and measles.

At the top of the immunization card was a blank for the name of her baby daughter. According to a long-held Ethiopian custom, parents wait to name their children because disease is rampant, health care is sparse, and children often die in the first weeks of life. Sebsebila didn't receive her own name until several weeks after her birth. And when her first daughter was born three years ago, she followed tradition and waited a month to bestow a name, afraid her child would not survive.

But a lot has changed in Ethiopia since the birth of Sebsebila's first child. This time, with more confidence in her new baby's chances of survival, Sebsebila didn't hesitate to name her. In the blank at the top of the vaccination card, she put "Amira"-"princess" in Arabic. Sebsebila's newfound optimism is not an isolated case. Ethiopia's effort on health has lowered child mortality over 60 percent since 1990, putting the country on track to achieve this important MDG target by 2015 and giving many parents the confidence to name children the day they are born.

Stories of progress like this underscore the importance of setting goals and measuring progress toward them. A decade ago, there was no official record of a child's birth or death in rural Ethiopia. At the Germana Gale Health Post, I saw charts of immunizations, malaria cases, and other health data plastered to walls. Each indicator had an annual target and a quarterly target. All this information goes into a government information system to generate regular reports. Government officials meet every two months to go over the reports to see where things are working and to take action in places where they aren't.

Yet while measurement is critical to making progress in global health, it's very hard to do well. You have to measure accurately, as well as create an environment where problems can be discussed openly so you can effectively evaluate what's working and what's not. Setting targets for immunization and other interventions can motivate government health workers, but it can also encourage over-reporting to avoid problems with supervisors.

Ethiopia's recent effort to monitor the progress of its immunization program is a good example of learning from data and-the hardest part-using data to improve delivery of the right solutions. A recent national survey of Ethiopia's vaccination coverage reported vastly different results from the government's own estimates. Ethiopia could have ignored this conflict and reported the most favorable data. Instead, it brought in independent experts to understand why the measurements were so different. They commissioned a detailed independent survey that pinpointed geographic pockets of very high coverage-and very low coverage. The government is now working to develop better plans for the poorer performing regions.

The progress Ethiopia is making on the MDGs is now capturing the attention of its neighbors. Much like Ethiopia, which learned from the Indian state of Kerala, other countries including Malawi, Rwanda, and Nigeria are now rolling out health extension programs after visiting Ethiopia to learn from its experience.